Morocco’s renowned Kasbah du Toubkal has racked up a three-decade record for good stewardship and community relations. Few lodges have had such a profound impact on their surrounding communities. During a visit, Jonathan Tourtellot learns how this came to be.

Mountain Lodge Shows What It Takes to Marry Success with Good Stewardship

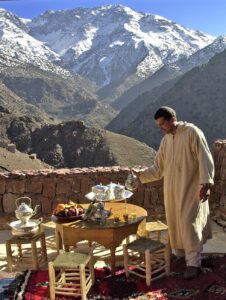

December 2024, Morocco – In the dining room of the Kasbah du Toubkal, we guests have been alerted that there would be some kind of local celebration after dinner. The remnants of lamb and chicken tagine and vegetable couscous have been cleared from knee-high tables, and now a ruckus arises out in the hallway. A sonorous masculine chant and a swelling of drums and tambourines heralds and a dozen or so men in djellabas who come trooping into the room. They form a circle, dancing, drumming, clapping, and singing away in the local Berber language. Now and then a different chant leader steps forward and starts a new round of chants.

We have no idea what is going on, but it sure is impressive.

The stone-walled Kasbah – the name means a small fortress or compound – grew from the remnants of a regional sultan’s summer villa in Morocco’s High Atlas Mountains during the days of French rule. Since its beginning as a trekking lodge back in 1995, the lodge has built a reputation for authenticity, sustainability, and excellent relations with the seven villages of the Imlil valley. Rarely has a tourism business done more for its locale. Each of us guests pays a 5% surcharge to benefit the communities. With most of the staff and guides recruited locally, the lodge can offer an authentic tourism experience. Sometimes mysteriously authentic.

Next morning, we learn that what we had seen was an ahwach, a kind of traditional dance and poetry slam. And, as we’ll discover, it’s also a mechanism of collaboration.

Can other entrepreneurs and destinations learn from the Kasbah’s exemplary experience? After all, its 30-year success stems from an unusual set of circumstances:

- A foreign visionary,

- A trusted, hard-working local partner,

- A major motion picture production,

- And a local culture with a tradition of collaboration.

Nevertheless, valuable lessons appear within each element of this story.

The Visionary Ex-pat

I asked cofounder Mike McHugo about each of these as we reviewed the Kasbah’s history.

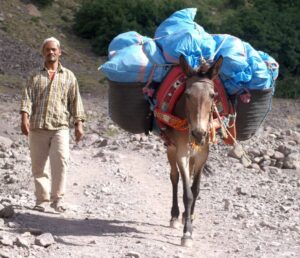

McHugo is the visionary Englishman who fell in love with the High Atlas. Climbing routes to Jebel Toubkal – at 13,671 feet, the tallest mountain in north Africa – begin down at about 5,700 feet in the Imlil valley. [4,167 and 1,737 meters respectively] When he first saw Imlil in 1978, the seven villages scattered along the steep slopes of the valley were impoverished, with no paved road access, no running water, no phones nor electricity – a realm for adventure travelers only.

An avid trekker, McHugo saw opportunity: Transform the chieftain’s old place into a kasbah, a symbolic fortress that protects the trails into Toubkal National Park and its snow-capped peaks.

In a story now well documented in Derek Workman’s 2015 booklet, Reasonable Plans, McHugo joined with his brother, Chris, and other investors to begin work. They teamed up with a trusted local partner – a wiry bundle of controlled energy nicknamed Hajj Maurice from his fondness for the pilgrimage to Mecca. Well-respected locally, Omar Ait Bahmed (his real name) was known for getting things done. He served as a critical liaison with the local villages and took charge of transforming what was initially a trekking dorm into what would become an upscale mountain lodge.

The McHugo approach was to use local materials, hire local labor, reflect local culture. “Their ultimate goal,” writes Workman, “was not just to make money, but to make the building as unique as possible, respecting tradition.” (I recall the decorative carvings that enhanced the beams in our ceiling and the solid wooden door to my room.)

The Major Motion Picture

Then a catalytic event occurred: Disney’s scouts for the 1997 Martin Scorsese film Kundun — the story of the Dalai Lama’s escape from Tibet — wanted the Kasbah to play the role of the monastery of Dunkar, where he found refuge.

McHugo agreed, subject to his rules of engagement during the six-week shoot: all local labor, all local materials, and, oh yes, a 5% surcharge to benefit the seven local communities. His rationale: “The tourist tax that the government collects goes too far away for local people to see the benefit of it.”

Now locals had to decide how to spend their windfall. To do so, they formed the Association Bassins d’Imlil, (Association of Villages of the Imlil Valley), a remarkable example of tourism-driven collaboration. The first project was a massive, much-needed trash clean-up for the valley. Since then, the Association has funded more rubbish clean-ups, two ambulances, a boarding house for girls to attend school, a new road, an irrigation channel, and a community hammam – the Turkish-bath style facility central to Moroccan culture.

The movie shoot launched a community-surcharge policy that would stick with the Kasbah onward.

The Villagers of the Valley

I ask assistant manager and Imlil native Lahcen Igdem how seven villages all agreed to create an umbrella organization? “We are used to cooperating with each other,” he says, explaining that the villages traditionally pitch in to help each other whenever the need occurred, whether comfort of a bereft family, the celebration of a wedding, or the gathering of a harvest.

The lodge-valley relationship has stood the test of time. Recruiting staff locally has enriched the whole destination. “All the guides who have worked here have been successful. They reached their dreams,” says Igdem. “This place is a school” – in effect, an on-the-job training center whose “graduates” have thriving guiding businesses, B&Bs, or good jobs elsewhere in Morocco. Among the large families typical of the valley, he says, almost every household will now have at least one person working in tourism.

Can the Same Approach Work Elsewhere?

Is the Kasbah du Toubkal a fluke, its success dependent on four lucky prerequisites? What if a place doesn’t have a visionary principled outsider (McHugo), a dedicated local partner (Hajj Maurice), a catalytic event (the movie shoot), or a collaborative, welcoming culture?

I offer my own thoughts about the first prerequisite. The world offers numerous examples of tourism businesses initiated by foreigners who fell in love with a place and wanted to do well by its people. While less frequent, the same has also been achieved by an entrepreneurial local with similar values, often one who has lived abroad long enough to bridge the cultural gap.

I put the remaining three prerequisites to McHugo:

“Could you have done this without Hajj Maurice?”

“Not with my skill sets,” says McHugo, “having someone with deep local contacts was very, very key to what we’ve done.” Not to mention being a skilled hard worker, Hajj Maurice has continued with the Kasbah since its founding, even overseeing reconstruction after the 2023 earthquake. “A local trusted partner is key.”

“Could you have done this without Kundun?”

Probably yes, suggests McHugo. He cites the historic boutique hotels called riads in Marrakesh, which could team up to apply the community surcharge. “Two or three or four in a street could form their own association so that people can see where the money goes.”

I ask whether competing accommodations can undersell you by not charging the 5%? McHugo calls this the “fallacy of the race to the bottom.” The Kasbah clientele is fairly affluent, and of the type likely to understand and approve the levy.

Ironically, Kundun was never widely seen. Bending to pressure from Beijing, Disney never distributed the movie widely and has since virtually suppressed it. Still, if you look hard online, you’ll find it.

“Could you have done this without the local Berber culture?”

Clearly, it helped. McHugo calls the villagers “naturally hospitable.” Elsewhere, it would of course depend on the social attitudes of the locale. Many indigenous and some developed cultures have often welcomed and worked with lodges like the Kasbah. Still, the Imlil locals display especially well-honed ways of working together.

On my last day, I learn from the other assistant manager, Hassan Ait Lcaid, that one way the villages can iron out mutual problems is during an ahwach. He tells how one village’s chant leader will improvise a poetic problem statement, and his counterpart a possible solution.

I try to imagine how this would work in English: “We need more water downstream [drums, drums], but getting it seems just a dream.” And then the reply: “We’ll open our dam two days a week. [More drums.] Will that supply all that you seek?”

Maybe the United Nations should try the approach.

————-

Jonathan Tourtellot is the executive editor of the Destination Stewardship Report.