Improving relations between a national park and its gateway communities can be tricky, involving touchy issues such as invasive species, extractive industries, air pollution, visitation levels and economics, even dark skies. The collaborative approach employed for North Dakota’s Theodore Roosevelt National Park yielded actionable community ideas and opened lines of communication while still upholding park conservation goals. The technique? Accentuate the positive with the approach called Appreciative Inquiry. Kelly Bricker’s University of Utah team explains how it worked.

For Theodore Roosevelt National Park, “Appreciative Inquiry” Provides a Way to Improve Relations with Its Three Gateway Towns

By Kelly Bricker, Leah Joyner, and Qwynne Lackey

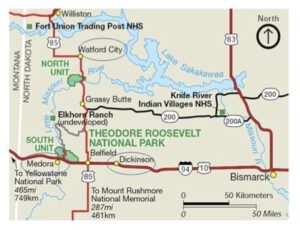

Theodore Roosevelt National Park (TRNP) encompasses two swaths of North Dakota Badlands, stretching across the Northern Great Plains and the Little Missouri River. The park was established in 1947 with the initial South Unit and Elkhorn Ranch Unit, and the addition of the North Unit followed in 1948. Its 70,447 acres comprise a variety of great plains flora (e.g., juniper woodlands and hardwoods, salt grass) and fauna (e.g., bison, elk, and pronghorn) as well as traditional lands of the Hidatsa and Mandan tribes, and many more. The Park memorializes President Theodore Roosevelt and his commitment to conservation[i]. It is also situated atop the Bakken Formation, an extensive oil and natural gas reserve tapped by hydraulic fracking, rendering oil and gas flares within sight of many park vistas[ii].

Figure 1. Theodore Roosevelt National Park Map.[vii]

Figure 1. Theodore Roosevelt National Park Map.[vii]

Three primary gateway communities provide access to the Park: Dickinson, Medora, and Watford City. The largest, Dickinson, with a population of about 23,000, offers education, healthcare, museums, libraries, airport, and recreation centers.[iii] Medora, home to Park headquarters, is North Dakota’s top tourism destination, and much of its a year-round population of about 130 residents[iv]derives income from the industry[v]. Watford City is home to about 7000 residents, a population that has more than tripled in the decade following the Bakken Oil Shale rush, a massive influx of people and commerce that began around 2006[vi].

Unique though they are, the communities are intertwined with each other, the park, and the future development of the region. In anticipation of increased park visitation, the Bakken nearby oil development and associated infrastructure, invasive species and other regional ecosystem issues, Park management began a strategic planning process designed to incorporate a holistic understanding of visitor use with the unique needs of each of its gateway communities. Park staff were interested in the communities’ current relationships with the Park and how they could improve to provide a quality visitor experience, advance park goals, and develop and leverage partnerships.

Our University of Utah research team conducted a community engagement study on behalf of the Park from February 2017 to April 2018 to assist with the planning effort. Our focus was on the relationships between TRNP and its three gateway communities. What was the role of TRNP related to stimulating regional tourism? What did the gateway communities need? How could tourism’s spillover benefits enhance their economic conditions and quality of life, while still upholding the purpose and values of the park?

To find out, we used an Appreciative Inquiry (AI) approach. The method for helping to manage change strives to understand the relationships among conservation, livelihood, and sustainable tourism development[viii] [ix] [x] The idea is to elicit public participation in identifying positive qualities that make a destination unique, to analyze how these qualities work, and then build on them.

Our hope in conducting the AI process was to:

- Create a shared understanding of community development, tourism, and resource protection;

- Create a regional dialogue about using public land to improve local livelihoods through sustainable tourism development;

- Envision a collective future based on regional strengths in relationship to developing tourism, improving livelihoods, and protecting natural and cultural heritage resources.

For this project, we visited Park management, mapped assets of each community, interviewed key leaders and online surveys, focus groups with community members, summary meetings and a summit with all communities present. The Superintendent of TRNP attended these meetings, and introduced the strategic planning process they were undertaking – yet only weighed in if there were specific questions by participants. The process itself is forward thinking and did not allow participants to focus on the negative, rather really focus on the future – discovering what they have, dreaming about and envisioning a future, and then steps to realize that future. In part, AI asks participants to focus on what can be – envisioning a future. This particular strategy allowed us as facilitators to ‘park’ concerns separately, then head back to the questions at hand. As meetings progressed, we did see a willingness of participants to ‘let go’ of their individual issues and work with us on defining a future. By tabling the negative, there was room to think beyond the current situation and envision a future. Guiding questions led our discussions and surveys including:

Discovery

- What tourism assets do you have in and around your community?

- What type of tourism is working in your community?

- What kinds of activities do tourists undertake? Provide the best examples.

- What have you done to improve your community’s livelihood through tourism?

- What positive linkages exist now between tourism and the resources you have?

Dream

- Please close your eyes if you feel like it. How do you envision your community 25 years from now?

- Think about what “ideal tourism” means in your community for your children and grandchildren/for future generations.

Design

- Putting dreams into practice. What actions and strategies do you feel are needed to achieve these dreams? Where/What? How?

Destiny

- We have achieved or learned about tourism and its potential contribution to your community. What comes next?

- How can the outcomes and what we have learned to be sustained?

- How and where might these ideas be used in the future?

We found this methodology to be engaging, inclusive, and an opportunity to move the relationship between the park and its nearby communities into a forward-thinking, action-oriented collaborative process. The responses recorded during all interviews, meetings, and surveys were summarized and analyzed thematically by the research team.[xi]

What did this process produce?

Several themes resulted from interviews, surveys and meetings, which had spillover impacts on sharing destinations resources and ideas. Following are some of the most prominent themes and their associated actionable ideas moving forward.

Conservation Awareness

Participants from all three communities value conservation. The viewshed and dark skies preservation was particularly important. Ideas for preserving the view-shed and dark skies included educational programs within the communities and establishing local ordinances.

For example, Medora suggested implementing more local ordinances to protect existing open-spaces.

Dickinson residents also desired a recycling program and the use of the Outdoor Heritage Fund, which provides grants for conservation in North Dakota[xii], to help develop recreation opportunities at Patterson Lake.

In addition some areas touched on regional conservation efforts, beyond park boundaries.

Actionable Ideas:

C 1. Develop programs that educate and empower residents to play a role in local conservation, such as environmental education programs, information sharing, and youth engagement.

C2. Launch an education program to inform neighboring community residents about the natural management of prairie dogs and other species within the park borders.

C3. Identify a mechanism for community input into the development of a feral horse management plan.

C4. Increase mechanisms for TRNP and Community-level engagement. Example: Park volunteer days (themed) and Adopt-a-Spot programs-whereby people might pick up litter or help with invasive species eradication, etc.Strategic Partnerships

Community meeting participants identified a diverse collection of potential strategic partners to work with on realizing many of the goals mentioned throughout the visioning process. Medora residents suggested partnering with local authors to advance their goal of educating visitors about the history of the area. They also suggested that increased partnerships with the other gateway communities would strengthen tourism across the region.

These included local university collaboration, CVBs, community centers, libraries, adjacent public land managers, associations and foundations.

Actionable Ideas:

SP1. Grow partnerships with DSU; if partnerships are occurring take advantage of marketing opportunities to publicize educational collaboration.

SP2. Develop a ‘friends of the park’ email communication list or listserv through which to reach all potential partners with any future development or support needs.

Tourism Management

Common to all community meetings was a continued emphasis aspects of visitor management and tourism development. For example, there was interest in fostering the ‘Old West’ themed tour development and continue focusing on both Native American and cowboy culture; local food; equestrian and non-motorized trail activities. Transportation efficiencies were also noted, such as a park shuttle to decrease visitor traffic, and enhancing activities for longer stays and some interest in seasonal expansion as well.

Actionable Ideas:

TM1. Explore options for transportation and infrastructure support, such as park shuttles.

TM2. Partner with local authors to enhance storytelling efforts such as events, guided tours, and interpretation within the park.

TM3. Conduct research on other national park gateway communities for innovative solutions and best practices elsewhere that have responded to limited workforce and seasonal housing barriers.

Youth Engagement

Participants in all communities expressed a strong desire for more youth-oriented activities and engagements. Dickinson residents specifically suggested integration with school curriculum, through field trips and library programs, as well as partnerships with the DSU Honors program. In Watford City, suggestions included leadership education, afterschool programs, and more community-based projects for youth to engage. Watford City residents also suggested seeking private or corporate sponsorships for programs that would better engage youth with TRNP.

Actionable Ideas:

YE1. Partner with educational institutions (such as DSU) to increase use of and further align the existing TRNP curriculum guides with state content standards.

YE2. Explore the possibility of a Youth Ranger program. Engage students through signing up to leading guided hikes, volunteering to visit campsites and share information with visitors, or for clean-up events within TRNP.

In summary, the AI method provided an excellent platform to launch new ideas, increase collaboration, and ensure avenues for information sharing. AI marked the beginning of a much longer process that may lead to sustained improvements in the relationships between the park and communities and changes in attitudes in all parties. We believe that AI provided the necessary process to focus on the future. We also felt it served as a forward-thinking and opened the door to future collaborative processes that address issues, such as retaining dark skies, and other natural resource concerns, such as air pollution, feral horse populations, and work on invasive species. For the complete report on the process and associated outcomes, please download: https://app.box.com/shared/static/8tsc9qedi22jfudhltpz6yhj0yjmy27h.pdf

[i] National Park Service. Theodore Roosevelt National Park. Foundation Document: 2014. Available online: https://www.nps.gov/thro/learn/management/upload/Theodore-Roosevelt-National-Park-Foundation-Document-2014.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2019).

[ii] National Parks Conservation Association. Spoiled Parks: The 12 National Parks Most Threatened by Oil and Gas Development. Available online: https://www.npca.org/reports/oil-and-gas-report (accessed on 20 September 2019).

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] United States Census Bureau. Available Online: https://www.census.gov/en.html (accessed on 15 September 2019).

[v] Medora Convention and Visitors Bureau. Medora, North Dakota. Web. Available online: https://www.medorand.com/ (accessed on 15 September 2019).

[vi] Nicas, J. Oil Fuels Population Boom in North Dakota City. Wall Str. J. Available online: https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052702304072004577328100938723454?mod=googlenews_wsj (accessed on 15 September 2019).

[vii] National Park Service. Theodore Roosevelt National Park Maps. Available online: https://www.nps.gov/thro/planyourvisit/maps.htm (accessed on 26 October 2019).

[viii] Nyaupane, G.; Timothy, D. Linking Communities and Public Lands through Tourism: A Pilot Project; Technical Report; Arizona State University: Tempe, AZ, USA, 2013.

[ix] Che Aziz, R. Appreciative inquiry: An alternative re-search approach for sustainable rural tourism development. J. Tour. Hosp. Culin. Arts 2013, 5, 1–14.

[x] Cooperrider, D.; Whitney, D.D.; Stavros, J.M. The Appreciative Inquiry Handbook: For Leaders of Change, 2nd ed.; Berrett-Koehler, B.K., Ed.; Crown Custom Pub: Brunswick, OH, USA; San Francisco, CA, USA, 2008.

[xi] For more information on method specifics, please see the article published in Sustainability 2019, 11(24), 7147; https://doi.org/10.3390/su11247147).

[xii] Outdoor Heritage Fund. For more information, visit: https://www.ducks.org/north-dakota/north-dakota-outdoor-heritage-fund

This article was prepared by Dr. Kelly Bricker and Leah Joyner of the University of Utah, and Dr. Qwynne Lackey, SUNY Cortland University (fall 2020). She and her colleagues, designed and implemented this study as part of a larger project with Kansas State University and Theodore Roosevelt National Park.