A historic holiday island in Florida was succumbing to bland residential development with little regard for sustainability. In this case, it took a visionary leader from the private sector to turn things around. David Randle sums up six lessons from Anna Maria Island.

A historic holiday island in Florida was succumbing to bland residential development with little regard for sustainability. In this case, it took a visionary leader from the private sector to turn things around. David Randle sums up six lessons from Anna Maria Island.

Anna Maria’s Pine Avenue Restoration Project:

A Model for Sustainable Stewardship

As Anna Maria Island on Florida’s Gulf Coast became popular with tourists, retirees, and second homes, the town was in danger of losing its past charm, historic character, and its limited commercial district on Pine Avenue.

Pine Avenue’s history reaches back more than a century. In 1911 a steamer would bring tourists from St. Petersburg across the mouth of Tampa Bay to the City Pier on Anna Maria. Guests would walk the Pine Avenue promenade to the bathhouse on the other side of the island, where the beaches are. Later, that bathhouse became today’s Sandbar restaurant.

By the turn of the millennium, however, the spotty commercial district on Pine Avenue was languishing. Four lots had been converted from business to residential. When seven more lots went up for sale, Sandbar owner Ed Chiles, already an established leader in the community, and local businessman Mike Coleman became concerned. They could see the potential loss of the island’s business district, which neither thought the community could afford. Ed came up with a plan to buy the five lots and resort the historical nature of Pine Avenue.

The plan was to find 20 people who would each contribute $500,000 for this $10 million project, which Mike would supervise. The response was less than Ed had hoped. Only one other person was willing to come up with the $500,000. Not to be discouraged, they financed the project by leveraging $1 million they did have.

After meetings with private citizens and elected officials, a new vision was born for Pine Avenue. The consensus was that two story historic cottages would be the best way to reflect the culture, heritage, and nature of their town. The idea was to recreate the old historic promenade walk so that present and future generations of guests could experience a taste of Old Florida.

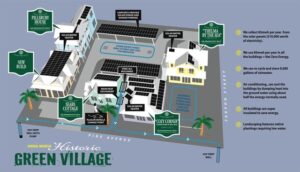

While the project was underway, it received a large boost from two more entrepreneurs. Mike and Lizzie Thrasher had recently retired from their business in the U.K. and took up residence in Anna Maria Island, where they had vacationed previously. The Thrashers purchased two of the lots from Ed and Mike and collaborated on supporting the restoration by creating the Green Village, a solar business district.

While the project was underway, it received a large boost from two more entrepreneurs. Mike and Lizzie Thrasher had recently retired from their business in the U.K. and took up residence in Anna Maria Island, where they had vacationed previously. The Thrashers purchased two of the lots from Ed and Mike and collaborated on supporting the restoration by creating the Green Village, a solar business district.

The Pine Avenue Restoration project is now complete. It includes historic architecture in sustainably designed buildings with boutique and retail shops on the first floor and tourism units on the second. Some of the project’s major sustainability features include:

- Building Construction used insulated concrete forms to develop buildings that use very little energy and can withstand 250-mph hurricane winds. The buildings were certified at the platinum level by the Florida Building Council. Construction manager Mike Coleman said one of the best compliments he received was when he overheard two women visitors commenting on “how good a job they did in fixing up these old buildings,” not realizing that the buildings were in fact brand new. Mike knew then that they had succeeded in restoring the historic sense of place.

- Energy Efficiency inside the building includes tankless on-demand hot water systems, energy-efficient appliances and lighting.

- Native Plantings were initiated by landscaper Mike Miller, another vacation visitor turned resident. After settling in, he became disenchanted with his too-lush garden of exotic plants, inappropriate to a barrier-island environment. He went through a personal transformation that turned him into a champion of native landscapes. He calls his approach “sense of place development.” Mike says, “Rather than change out the sand in order to accommodate exotic plantings, we plant natives for which the sand is the intended home. Rather than hardscapes and lawns that encourage runoff into our water bodies and, ultimately our precious Gulf and Bay, we leave sand wherever possible and create rainwater storage for capture and re-use.”

- Edible Gardens are placed all along Pine Avenue. The gardens were developed in partnership with ECHO, international experts on tropical agriculture. The ECHO edible gardens grow food on Pine Avenue year round. Local restaurants use some of it. The gardens have inspired residents to create gardens in their homes as well.

- Permeable Walkways have replaced concrete sidewalks on Pine Avenue. Guests and residents alike can stroll on them through the edible gardens and native plants. In the event of a tropical storm or hurricane, the combination of native landscaping and permeable walkways is estimated to reduce flooding by as much as 50%.

- Transportation – The Pine Avenue redevelopment has spurred some rethinking of transportation. Pedestrian pathways, bicycles, and golf carts are the norm for getting around town. Island visitors are encouraged to use a free trolley.

- Rainwater is gathered and stored in a 9000 gallon reservoir and used for both landscaping and the waste water system.

-

Solar Business District: The Historic Green Village shopping center includes both historic building restoration and new construction. Solar, geothermal, energy efficiency, and rainwater collection have helped the village to become one of 100 developments worldwide that have achieved the Net Zero Energy Buiilding Certification and LEED Platinum certification. The village produces more electric energy than it uses, sharing the excess with others on Pine Avenue outside the village. The Village goes even further in the preservation of historic buildings, including a lodge and the greening of their supply chain as well.

- Local and Sustainable Food – The anchor for this project is the Sandbar restaurant, known for its environmental commitment and sustainable practices. The Sandbar recently purchased its own farm to insure that it could get the type of produce it needs. Its seafood is sustainable, much of it purchased from the nearby Historic Cortez fishing village. In addition the Sandbar has joined with the Gulf Shellfish Institute to encourage production of shellfish used in their restaurant. The restaurant sometimes also taps the Edible Gardens and its own onsite garden. Other sustainable practices include oyster shell recycling to help restore reefs; elimination of plastic straws, lids, and bags; composting for use by the farm; and a program to put invasive lionfish and wild boar on the menu. The menu also features Grey Striped Mullet, a local heritage seafood that dates back to the Timucuan and Calusa Native Americans who once inhabited the island. The Sandbar has also teamed up with START and the Mote Marine Lab to find solutions to the challenge of intermittent red tides that can shut down businesses.

Lessons from Anna Maria Island

- Local leadership – It takes a person with passion and leadership like Ed Chiles for change to succeed. This project may not have happened without him. Good management is needed to implement the vision, and Mike Coleman played a critical role, paying attention to the details necessary to bringing the vision to fruition.

- Green planning – It’s important to incorporate environmental features in the initial design – less expensive than adding them later. For this project, green planning made the construction less costly, lowered ongoing operational costs, and increased the value of the end product.

- Community support – Rallying local support helped clear political hurdles and brought more people into the project.

- Openness and flexibility – Allowing the project to grow organically without controlling of every aspect enhanced this project greatly. Examples include willingness to collaborate with the Thrashers and their idea of the Green Village, utilizing Mike Miller’s expertise in native landscaping, and getting local government support for features like the permeable walkway.

- Networking – Ed Chiles is a co-founder of the Blue Community Consortium, a UNWTO Affiliate and member of the UNWTO International Network of Sustainable Tourism Observatories. He is also on the boards for START and the Gulf Shellfish Institute. All three of these groups were invaluable in supporting and expanding the sustainability and heritage preservation vision of the project.

The relationships also have proven to be allies for the business to share the Anna Maria story, to find solutions to the threats of red tide that can shut down business, and the increased sourcing of shellfish for sustainability. When asked about the greatest success of this project, Ed said “I believe the most important component of the combined projects is their contributions toward elevating the discussion and implementation of sustainable practices in our community.” - Sustainable supply chains – A key element of success for this project was building relationships for a sustainable supply chain. While not every restaurant can purchase its own farm, there are ways to negotiate with farmers to ensure supply needs are met. Building relationships with the local fisherman has helped to insure a good supply of sustainable fish, and local aquaculture – replicable in many places around the world – helps relieve overfishing while creating jobs and strengthening the local economy.

The future of Anna Maria

By 2011, the Pine Avenue Restoration project was a success. Challenges and threats of course remain, such as the red tide events that come and go, as well as such global challenges such as climate change, pandemics, and economic ups and downs.

Aware that there will not always be an Ed Chiles, the community has begun to think about future transitions. Given all the networking that has occurred, coupled with the highly competent team in Ed’s organization, the chances for continuity are strong.

One thing that makes Pine Avenue so attractive for an educational model is that within a 15-20 minute walk, a visitor can see and experience all of the sustainability features I have listed. Anna Maria Island serves as a global model for sustainable tourism and continues to attract interest from around the world. View their Sustainability Management Plan and consider a visit someday yourself.